Monitoring & "Mono-ing" in Mixing

Est. Read Time: 7 mins

Alliteration’s Awesome, Ain’t It?

Well, that depends on who you ask. Repeating the same thing over and over can be unbearable to some. Just ask your roommate or significant other who is tired of hearing you spend hours perfecting that one mix. Repetition when mixing is necessary to identify the various areas of a sonic work that need to be adjusted to achieve a cohesive sound. However, while it is true that you cannot listen to a mix just once and make all the necessary adjustments, many music producers spend countless hours correcting elements of their mix but get nowhere in the process. Here are two simple yet often overlooked aspects of the mixing process that can help to improve your tracks.

MONITORING

Your monitoring environment can make or break your mix. Ideally, we would all mix our projects in an acoustically treated room. Realistically though, we all do not have access to such facilities. Solid monitoring practices, however, can still lead to great mixes. Here are a few tips to get the most out of your monitoring situation, especially if it is less than ideal.

1. Monitor Moderately

It's easy to crank up the volume when listening to a song you like, especially when it's your own. Almost everything sounds better when played loudly, so it's normal to increase the volume of music we like. However, although this natural tendency is okay during casual listening, the mixing process requires an impartial ear. Monitoring your mixes at moderate levels helps you better identify elements that either stand out too much or not enough. You can always check for things like bass presence and "oomph" by periodically turning up your volume, but when you solely mix at super loud levels, you only get a single, biased perspective of how your track sounds. Playing that same mix at lower levels will give a much more realistic sense of its quality. Does it still catch your ear, or is it a muddled mess of music? A mix that catches someone's ear at low levels encourages them to turn it up, making them like it even more.

If you want people to turn your music UP, turn the volume DOWN.

2. Reference Reality

Let's say you've produced a song, and now you're ready to mix. Firstly, you should ensure it was recorded in the best quality possible since the garbage in, garbage out (GIGO) theory applies as much to music production as it does to computer science. The various sounds in your mix should complement each other, and after settling on the general idea for the mix, you're ready to bring it all together. You should find an existing, well-mixed song that you want to emulate, especially when mixing in a poorly treated (acoustically) environment. The use of "reference tracks" is a well-known practice in the music production world, so it may seem like an unnecessary thing to cover. However, it can be a foreign technique to new producers and an overlooked strategy by more experienced ones. Comparing your track to a professional one of sonic similarity can help to negate some of the acoustic issues that may be present in your listening environment. In turn, you should be able to identify potential areas of improvement within your mix quickly. Remember, when referencing, choose reference material that is WELL MIXED and is representative of the genre and sonic style that you are targeting. Maybe you want to mirror the hard-hitting, gritty sound of the kick and the bass in J. Cole's "Fire Squad." Instead, you might be aiming for the overall pristine sound found in songs like The Beatles' "Here Comes The Sun" or Marvin Gaye's "What's Going On." No matter the style of music, emulating a well-mixed record will most likely help to improve your mix.

Overall, if you're having trouble tightening up your mix, try to reference an already great-sounding record that matches your record's target style.

3. Switch Sites & Speakers

Location, location, location. A key mantra in mixing, as much as it is in real estate. As previously mentioned, an acoustically treated environment is ideal while working on a mix but changing your listening environment is also useful when trying to achieve a great sound. Since most of your audience will not hear your record in the same place or through the same sound system, changing speakers and locations will help you to get a better idea of how your mix will translate to the "real world." Listen to your track through a variety of speakers. Listen through earphones, listen through your laptop speakers, and listen in your car. Identify the elements of your mix that are lacking when you hear it in different environments. Take notes, then go back to your workstation and tweak your mix to correct the issues you observed. By doing this tiny bit of legwork during the mixing process, you'll save yourself a ton of time and a ton of surprises. If your mix sounds great in one place, test it in a different listening environment to see if the quality still stands. Just don't go overboard double-checking!

MONO-ING

Ah, good ol' stereophonic sound. Many people know it as stereo, but few truly understand it. Stereo is a method of sound reproduction that creates an illusion of a multi-directional auditory perspective. Unlike monaural (mono) sound, which emanates from a single point source, stereo sound is used in audio to help sell the illusion of "sound in space." It is typically more representative of the way we hear sound in real life. One important thing to note is that mono sound outputs one channel or stream of audio information, whereas stereo sound outputs two streams. So, when you see the infamous YouTube comment that says, "my left ear enjoyed this," the audio was probably monaural and only playing out of the left channel of someone's stereo headset. Please don't be the person that produces content with this kind of audio. Thank you. Anyway, more on this later; on to panning.

The Power of Pitch & Panning

So we know that stereo sound consists of two channels of audio. With a standard dual-speaker stereo setup, one audio stream goes to the left speaker, the other to the right. Now, there are different ways of getting these separate channels of audio. One way is to record using two microphones so that each one picks up a slightly different version of the source material. By sending the information picked up by the first microphone to one channel and the information picked up by the second microphone to the other channel, we get a realistic sense of space. This setup emulates the way our ears naturally pick up sound. Another method of achieving stereo sound is less natural but is handy in a pinch. It involves duplicating a mono signal and panning one version to the left and the other to the right. By subtly altering the timing and pitch of one of the signals, the resulting audio will sound more "stereo."

Haas Help

As mentioned above, altering the timing of a secondary mono signal can make for a faux-stereo output. The Haas effect is a psychoacoustic phenomenon based on timing that can help emulate stereophony. The principle is simple: duplicate the mono signal as explained earlier and pan one hard left (100% left) and hard right (100% right). Then, delay one of these channels by up to 35 milliseconds, tricking the brain into perceiving depth and space within the mix.

So...why is mono-ing important?

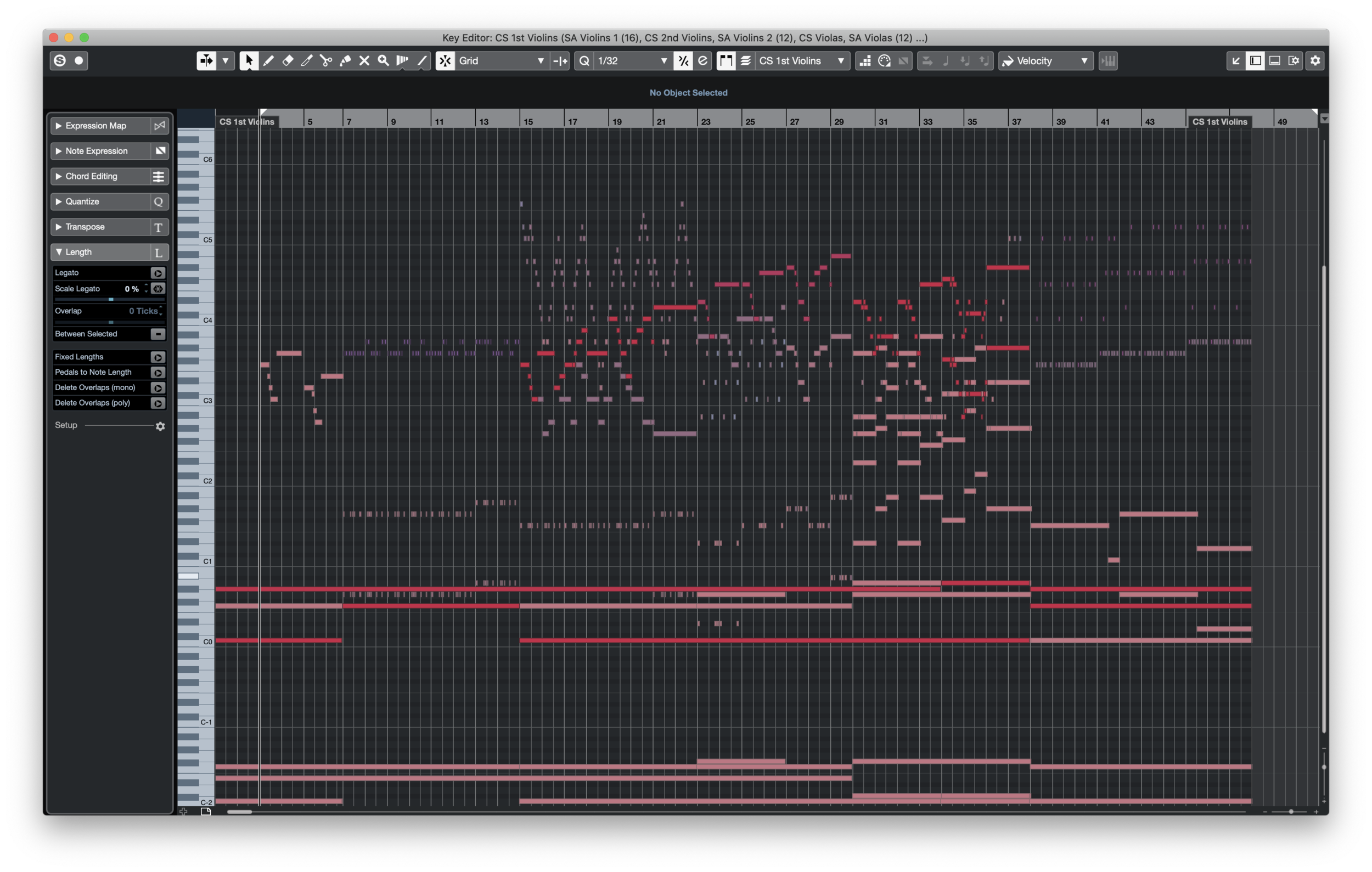

We've talked about stereo and how much time and effort is necessary to make a stereo mix sound great. Why then would we bother with "mono-ing?" Similar to the phenomenon where louder music typically sounds better, stereo material lends itself to a more immersive listening experience when compared to the same content in mono. Unfortunately, not all listening devices can produce sound in stereo, so to ensure your mix translates well when played through a mono system, you should practice periodic mixing in mono. Some digital audio workstations (DAWs), like Reaper, have a mono button on the master bus, while others, like Ableton, have plugins (Utility) to sum signals to mono. Hardware solutions like the Mackie Big Knob Passive have mono buttons that you can physically press to achieve the same result. A mix in mono will rarely hold a candle to its stereo version, BUT if you manage a solid mono mix, your record will most likely sound great no matter where or how it's played.

Now, with all this information, you should be at peace with your roommate, S.O., and your mix, so here's to happy mixing!

SUMMARY

Monitor Moderately: don't listen to your mixes too loudly for long periods.

Reference Reality: use reference tracks when mixing to help evaluate the quality of your work.

Switch Sites & Speakers: change your listening environment to ensure your mix "translates" well in different locations and sound systems.

Panning: pan your audio to give a sense of placement and directionality of sound sources.

Haas Help: use the Haas effect to introduce spaciousness when you need more depth in your mix.